- 4 Posts

- 17 Comments

My background is in permaculture but there’s significant overlap between that and solarpunk. My point of view is that permaculture and/or solarpunk work at the individual level. They work even better at the household level, and even better at the community level, even better nationally, and best internationally.

You don’t have to change the whole world to be successful. You’re not responsible for the entire world, only your own actions. So be a part of the solution, lead by example and persuade others to do the same. But you’re not expected to carry 8 billion humans on your shoulders, all the other animals, the trees, the weight of all of the oceans, etc. People only believe this because it gets repeated incessantly but take a step back and realize how obvious it is that you can’t be expected to be personally responsible for basically all of existence. You’re not omnipotent. Let go of weird expectations that anyway are probably promoted by fossil fuel types to overwhelm people into inaction.

Be responsible for your own actions, be part of the solution, and let go of the rest.

7·1 year ago

7·1 year agoSunZia is a megaproject by almost any measure. Pattern executives estimate that SunZia will generate enough power for three million homes. That’s three times as much energy as what’s produced by the largest wind farm currently in operation, the 1-GW Great Prairie Wind project in Texas. There are only six power plants in the entire country with a larger listed capacity than 3.5 GW.

Wow!

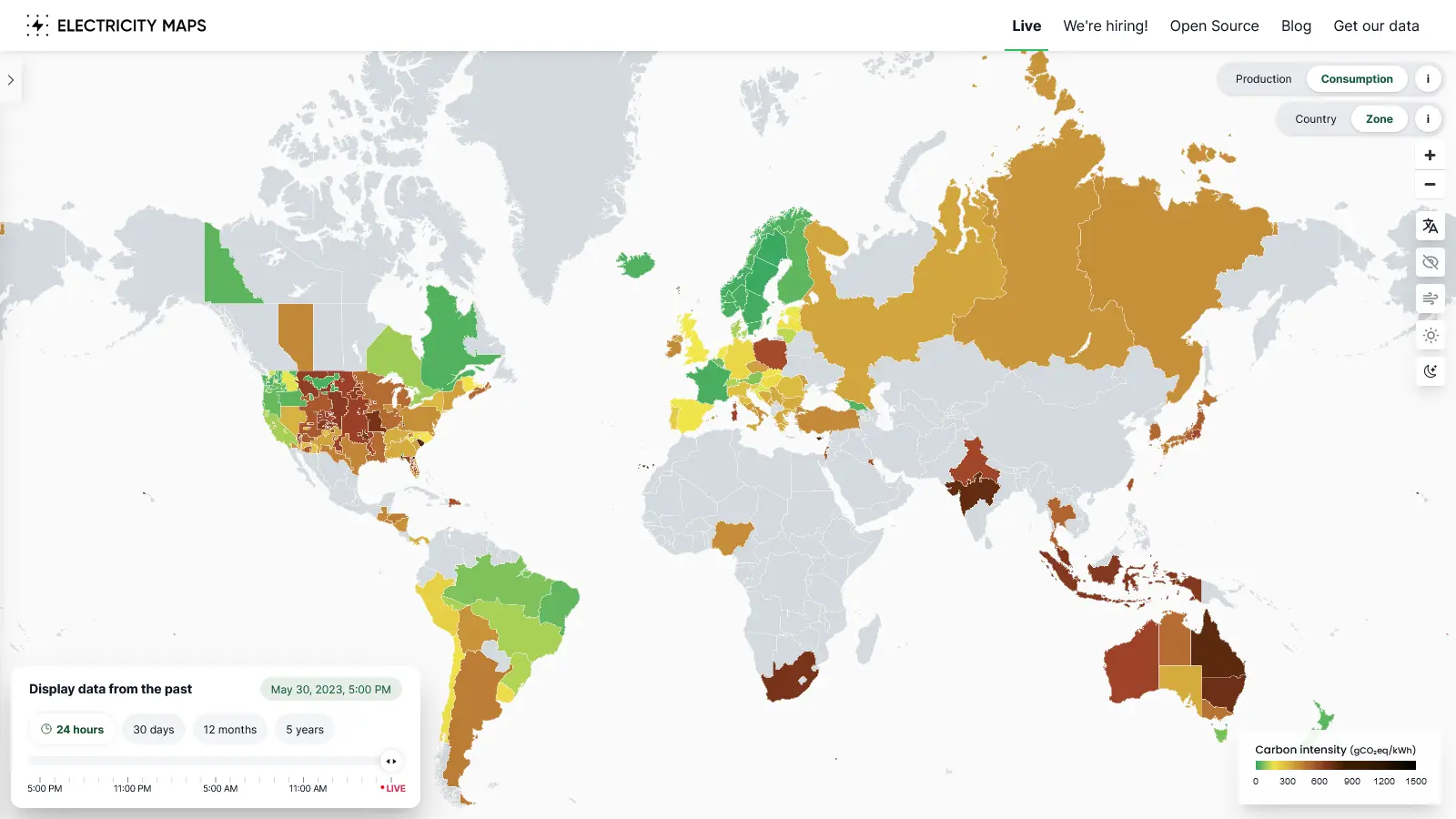

I would love it if we could treat this as a competition, to see who can build the lowest carbon-cost electricity service. A region of India has a competition like this, where villages do earthworks projects for rainwater infiltration and reforestation. The result is massive positive change. The same competitive spirit could be extremely powerful if applied to energy generation.

9·1 year ago

9·1 year agoYes!!!

Here’s a related, short video, from Brad Lancaster in Tucson, Arizona: How wall color can cool (or heat) you by over 25˚F (13˚C), & shade can cool you by over 45˚F (25˚C)

4·1 year ago

4·1 year agoWe use a simple homemade compost toilet, saving 150kg of climate change emissions per person each year, and instead of creating sewage, we create compost.

1·1 year ago

1·1 year agoHence why I said to purify it, and I only mentioned propane in the context of cooking, which is virtually if not always off-grid, so no piping.

2·1 year ago

2·1 year agoAs an additional (future) option, I love the idea of creating biochar, capturing the resulting syngas, and purifying the syngas for use as a plug-and-play alternative to propane compatible with their existing cookware.

I think this is sound from ecological and social standpoints. Propane is basically a byproduct of fossil fuel refinement, and as that goes away, so too, will propane, leaving behind a ton of wasted cookware etc. including the embodied carbon in its manufacture. By replacing the propane with another gas that’s a byproduct of sequestration rather than fossil emissions, we save the embodied carbon and financially incentivize sequestration, while the people with cultural attachments to gas cooking can continue on.

DNS, web, mail, WireGuard, etc. I wrote the webserver in about 700 lines of Go and the other software is by other people. Currently I’m rewriting everything in Rust and will write an authoritative DNS server in Rust. Eventually I want all my services to run on my own software (except for WireGuard, which is best in-kernel).

My first professional mailserver was around 1996, with 400 users, up to over 3000 users by 2001. It was awesome then but now mail is the last thing I’d recommend anyone self-host. The ecosystem has been deteriorating for decades at this point.

Pathogen destruction is a function of time and temperature. Generally speaking, a compost bin at 140F/60C for an hour will kill most pathogens, or 130F/55C for a day, or 120F/49C for a week. And generally, compost bins will hold a peak temperature for between 24-72 hours before slowly dropping again, while adding fresh material will make the temperature rise again. Part of the reason time matters is because it isn’t just heat that kills pathogens - it’s also compost microorganisms that physically kill pathogens in the bin.

Getting compost very hot like 160F/71C like you say will kill pathogens quickly but it’s not only unnecessary, it’s also harmful, as a lower temperature will result in a more diverse culture of bacteria in the finished compost. Personally I aim for about 140F/60C.

And anyway, note that I said above 120F. It sounded like the GP was having issues with their compost that made me think that 120F would be a reasonable target to shoot for given their current situation.

Love the biking and zazen!

I did really well last winter then got out of the habit when it got warmer (I have a thing about smells).

Can you describe your setup? A properly maintained compost bin doesn’t smell at all.

How to make one: take some fencing (you can get it for free from Craigslist) and make a bin a little over 1 meter tall and roughly 1 or 2m around, outside, on top of soil. Put dead dry plants or leaves inside on the bottom at least half a meter deep. That’s your sponge material to keep certain things from leaking into the soil. Now it’s ready to start taking inputs like toilet material, kitchen and yard scraps, dead animals, etc. Form a hole in the center with a pitchfork or other tool and put all inputs into that hole. Then put cover material on top of the freshly added material. Good cover materials are hay, straw or leaves, and they prevent smells. This cover material should also be present on the sides of the bin. Finally, get a compost thermometer and stick it in the middle of the material. The goal should be to get the temperature above 120F/49C. This will take a good amount of material and consistently adding it through the winter.

4·2 years ago

4·2 years ago- They are okay with men having normal recreational sex

- They attack women for having normal recreational sex

They want men to have sex with women, and they don’t want women to want it. They are pro-rape of women.

1·2 years ago

1·2 years agoHere’s a video showing Brad Lancaster’s permaculture house in Tucson, AZ:

https://youtu.be/KcAMXm9zITg?t=1715

I linked directly to a spot showing him getting good water pressure with only 2.5 feet (less than a meter) of head.

In other parts of the video he talks about filtration. You can watch the video yourself, it’s awesome. I hope it inspires you.

It sounds like the place you lived is not a great example of rainwater harvesting and greywater, like they didn’t really know what they were doing and cobbled together something mediocre. Do you think that water issues in Flint, Michigan are an indictment against the conventional water system? Or in India? I don’t blame you for having a bad personal experience with something and concluding that that thing is bad. That’s just how it goes. But take a step back and realize that the questions you have are solved problems. It’s just that most people are unaware and many are resistant to change.

The fact that the conventional water system is starting to run out of water in some desert areas, and that the problem is growing, is proof in itself that this system is unsustainable. So we need less pushback and more engaged interest.

Quoting Wikipedia from the Central Arizona Project article:

“The 456 billion gallons (1.4 million acre feet) of water is lifted by up to 2,900 feet by 14 pumps using 2.5 million MWh of electricity each year, making CAP the largest power user in Arizona.”

That is not simple at all.

“The canal loses approximately 16,000 acre-feet (5.2 billion gallons) of water each year to evaporation, a figure that will only increase as temperatures rise.”

43·2 years ago

43·2 years agoI think you’re best suited to answer your own question. Since you’re the one who wants to build nuclear, why don’t you do it?

If the answer is expertise, no problem, just hire people.

If the answer is money, just band together with others. Online discussions always have tons of people who want the same thing you do – you can pool your resources.

1·2 years ago

1·2 years agoYou can ask him, or read his book. He’s spent decades working on water.

Have you installed and used rainwater harvesting and greywater systems? It sounds like you haven’t. They’re remarkably simple.

1·2 years ago

1·2 years agoDoable but not necessarily with a lower impact.

According to Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond (volume 1, 3rd edition) by Brad Lancaster, page 249, an example household doing water harvesting and reuse, saves between 80kWh and 97kWh per month and between 174 pounds (78.8kg) and 211 pounds (95.5kg) of CO2 emissions. That’s a huge win for rainwater harvesting and greywater.

Rooftop solar and wind also save a ton of water since traditional generation methods of burning fossil fuels need lots of water.

And according to the same book, page 240, here are some kWh/gallon ranges of various water sources:

- on-site rainwater: 0.0000 to 0.0007 kWh/gal

- on-site greywater: 0.0000 to 0.0002 kWh/gal

- groundwater: 0.0006 to 0.0020 kWh/gal

- avg utility water: 0.0011 to 0.0041 kWh/gal

- brackish groundwater: 0.0032 to 0.0379 kWh/gal

1·2 years ago

1·2 years agoI agree but just want to add that at least some people in apartments and condos can still produce and use solar-generated electricity. Here’s a cool example:

Although I have rooftop solar producing around 200% of our usage annually, I was inspired by this story and have been increasingly using our offgrid LFP (LiFePO4 / lithium iron phosphate) backup batteries with solar panels to power certain things.

I think people in apartments would need rooftop access (ideally), equator-facing windows or a balcony, at the very least, for this to make ecological sense as there’s a carbon cost to manufacturing batteries and solar panels. But it’s doable and some people are doing it!

Here’s another:

3·2 years ago

3·2 years agoTucson, Arizona in the Sonoran Desert receives more rainfall annually than the amount of water sourced municipally. In other words, even in a desert city like Tucson, there’s no need to import water. We are wasteful not by nature but by habit, and that can be changed. Rainwater harvesting with thoughtful usage, mulching and locally-appropriate plants and greywater provide all the water necessary except in the most extreme environments such as Death Valley. But even in Death Valley a single family home could provide all its own water through the above if they were also doing solar distillation and reuse.

With proper management and cultural development, cities can provide all their own water and energy and a substantial portion of food.

I’m active in that community but agree there’s too much negativity there, and too much negativity in general. It seems to be improving over time, though.