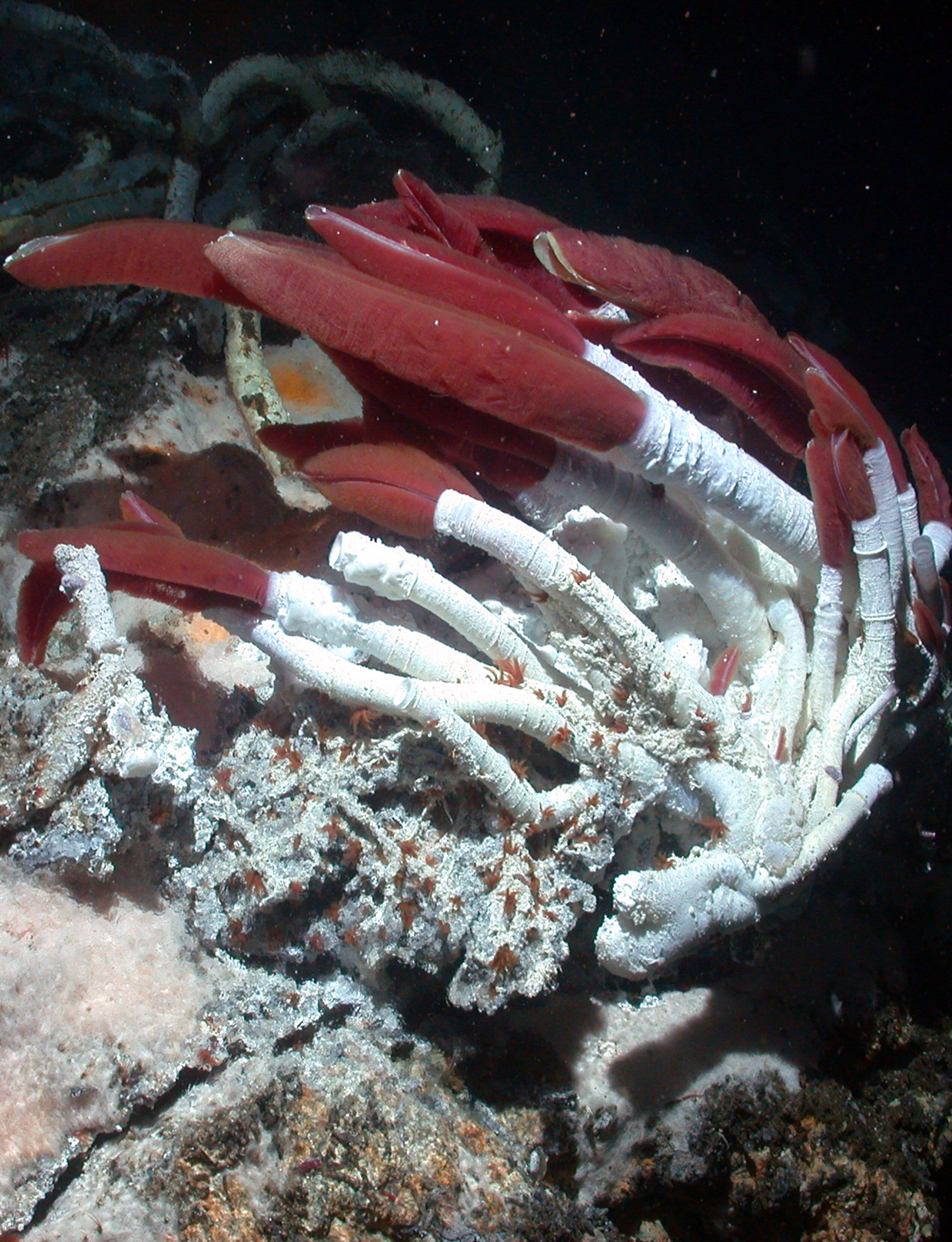

In the deep-sea environment of the East Pacific Rise, where sunlight does not penetrate and the surroundings are known for their extreme temperatures, skull-crushing pressures, and toxic compounds, lives Riftia pachyptila, a giant hydrothermal vent tubeworm. Growing up to 6 feet tall with a deep-red plume, Riftia does not have a digestive system but thrives off its symbiotic relationship with bacteria that live deep within its body. These billions of bacteria fix carbon dioxide to sugars to sustain themselves and the tubeworm.

Carbon fixation is the process of converting carbon dioxide to sugars, and it is the primary process that keeps our biosphere running. Depending on the environment, including available energy and carbon sources, organisms have evolved different metabolic strategies. Photosynthetic organisms, like plants, use sunlight to provide the energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen.

In the deep sea, beyond the reach of sunlight but where volcanically superheated water is gushing through hydrothermal vents, Riftia pachyptila’s chemoautotrophic symbionts use energy from hydrogen sulfide to fix carbon that fuels the metabolism and growth of the worms.